A world with evolving roots. For Alba Zari, roots are a point of personal exploration. We met her in Trieste and appreciated the simplicity and immediacy that emerge from her most intimate works, such as the beautiful book The Y (Witty Books, 2019), a visual narrative that reveals aspects of her ongoing search.

Alba Zari, photographer and documentarist, was born in Thailand where she lived until the age of 8. In Italy, she first lived in Trieste, then in Bologna, where she graduated in Cinematography from DAMS, before specializing in photography and visual design at NABA, Nuova Accademia di Belle Arti in Milan. She continued her studies in documentary photography at the International Center of Photography in New York. In her works, there is deep reflection and artistic sensitivity, along with an approach to the complexity of the human mind and a constant dialogue between the past and present, memory and innovation, between the human and AI, truth and authenticity.

Alba Zari will also be a lecturer at Visual Hub with the course Il vaso di Pandora. Un approccio concettuale all’archivio (Pandora’s Box: A Conceptual Approach to the Archive), which will be held on October 5-6 at Stage21 Trieste.

You have a nomadic life. What do you consider your roots?

My roots are the place where my loved ones live. Since part of me remains unknown and will probably always be a mystery, Trieste is the place I consider home and that feels familiar to me. The beaches of Thailand, on the other hand, evoke the sensations of my childhood.

Your first childhood memory, and whether you think this memory is affected by photographic memory or not.

My first childhood memory is related to what my mother remembers. She was hanging the laundry, and I, at the age of two, was handing her the clean clothes. We were in Bangkok.

Your thesis at DAMS focused on photography after Law 180, and this year marks the 100th anniversary of Basaglia’s birth. What do you remember about it?

My thesis at DAMS dealt with the evolution of photography related to psychiatry after the approval of Law 180, the so-called “Basaglia Law.” This law, enacted in 1978, marked the closure of asylums in Italy and represented a revolution in the treatment of people with mental disorders. My research focused on how photography was used both to document the conditions in asylums before the law and to tell the story of the social and cultural change that followed, through archival material. The images from this period are powerful and often disturbing, as they depict the inhumanity of the old institutions and, later, the attempts to restore dignity and humanity to the patients. A significant example is the work of photographers like Carla Cerati and Gianni Berengo Gardin, who in 1968 created the project “Morire di classe,” a reportage that documented the dramatic conditions of Italian asylums and had a strong impact on public opinion, contributing to the mobilization for reform. After Law 180, photography continued to play a crucial role in documenting the transition to a new psychiatry, more open and inclusive, with projects that aimed to show the faces and stories of people once confined and marginalized. These photographic projects not only documented reality but also had an ethical function, questioning the viewer and encouraging reflection on themes of freedom, dignity, and inclusion. The centenary of Franco Basaglia’s birth offers a valuable opportunity to reconsider the impact of these images and their role in supporting social change. I then photographed the mental health centers in Trieste the year of my graduation to show the change over time in the places where Basaglia’s revolution took place. A few years later, during my master’s at NABA, Nuova Accademia di Belle Arti in Milan in Photography and Visual Design, I re-photographed the users of the CSM (Mental Health Centers) and named the work I Prescelti (The Chosen Ones).

My thesis at DAMS dealt with the evolution of photography related to psychiatry after the approval of Law 180, the so-called “Basaglia Law.” This law, enacted in 1978, marked the closure of asylums in Italy and represented a revolution in the treatment of people with mental disorders. My research focused on how photography was used both to document the conditions in asylums before the law and to tell the story of the social and cultural change that followed, through archival material. The images from this period are powerful and often disturbing, as they depict the inhumanity of the old institutions and, later, the attempts to restore dignity and humanity to the patients. A significant example is the work of photographers like Carla Cerati and Gianni Berengo Gardin, who in 1968 created the project “Morire di classe,” a reportage that documented the dramatic conditions of Italian asylums and had a strong impact on public opinion, contributing to the mobilization for reform. After Law 180, photography continued to play a crucial role in documenting the transition to a new psychiatry, more open and inclusive, with projects that aimed to show the faces and stories of people once confined and marginalized. These photographic projects not only documented reality but also had an ethical function, questioning the viewer and encouraging reflection on themes of freedom, dignity, and inclusion. The centenary of Franco Basaglia’s birth offers a valuable opportunity to reconsider the impact of these images and their role in supporting social change. I then photographed the mental health centers in Trieste the year of my graduation to show the change over time in the places where Basaglia’s revolution took place. A few years later, during my master’s at NABA, Nuova Accademia di Belle Arti in Milan in Photography and Visual Design, I re-photographed the users of the CSM (Mental Health Centers) and named the work I Prescelti (The Chosen Ones).

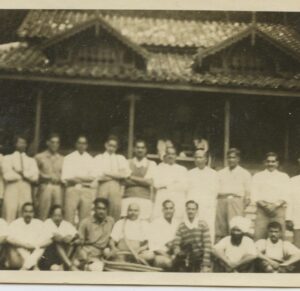

In your work Rakshasa (Rakshasa, Exploring Mental Health and AI at UNITS, Trieste), mental illness, particularly schizophrenia, is explored. Could you share a thought process/parallel with artificial intelligence? Can you tell us about your relationship with AI and how, if at all, you integrate it into your photographic research? In the realm of contemporary art, where symbolism and metaphor often serve as powerful channels for expression, an installation emerges that speaks to the intersections between human consciousness and artificial intelligence. The term Rakshasa, derived from Hindu mythology, refers to a malevolent demon, a fitting metaphor for the darker aspects of the mind. The installation presents four white sheets adorned with images of demonic visions, symbolizing the intrusion of mental health issues, particularly schizophrenia, into the fabric of human experience. Simultaneously, within the “Walls”, a monitor displays a video of AI-generated images derived from a family album discovered in New Delhi in 1932, emphasizing the symbiotic relationship between mind and machine. This narrative embarks on a profound exploration, weaving together the complexities of schizophrenia and the ever-evolving landscape of artificial intelligence, revealing a tapestry that blurs the boundaries between perception, memory, and machine-generated visions.

Exploring the depths of mental health, particularly schizophrenia, reveals the marvel of the human brain, a highly complex and interconnected organ. Schizophrenia disrupts the delicate balance of neural networks, leading to symptoms such as hallucinations, delusions, and disorganized thinking. This disruption mirrors the intricate web of connections within the human brain. Similarly, advanced artificial intelligence systems, particularly neural networks, mimic the interconnected nature of the human brain. The intrinsic complexity of these systems sometimes leads to unpredictable behaviors, akin to the disruptions observed in mental health. Therefore, the juxtaposition of the intricate networks of the mind with the artificial complexity of neural networks offers a profound metaphor for the shared complexities between schizophrenia and AI. The course of schizophrenia is characterized by its erratic and unpredictable nature, with symptoms varying widely between individuals. The non-linear progression of the disorder makes it difficult to anticipate the trajectory of symptoms. This unpredictability finds a parallel in AI algorithms, particularly those employed in deep learning. The elusive nature of their decision-making processes introduces a level of unpredictability comparable to the blurred manifestations of schizophrenia. The metaphorical “Walls” of the installation, adorned with demonic visions, become a canvas upon which the non-linear trajectories of both mental health and artificial intelligence unfold.

Within the artistic installation, the metaphorical “Walls,” where demonic visions and AI-generated images converge, push for a deeper exploration of the symbiotic relationship between the mind and the machine. The installation, which depicts the mind overtaking reality through images of demons, draws a parallel with AI’s ability to reinterpret memory, creating alternative visions that act as extensions of the human mind. The metaphorical intersection serves as a meeting point where the complexities of human cognition intertwine with the transformative power of artificial intelligence.

The metaphorical “Walls” transcend the physical space of the installation, inviting reflection on the evolution of the relationship between the human mind and artificial intelligence. At this point of convergence, where demonic visions and AI-generated images meet, a tapestry unfolds that reflects the intricate web between reality, perception, and the vast realms of the mind and the machine. The installation serves as a poignant reminder of the nuances and shared complexities that define the human experience and the evolving landscape of artificial intelligence.

You named your documentary White Lies. As Kant argued, a lie remains a crime even when told to a murderer asking if we are hiding a friend from him. What is your relationship with lies?

I agree with Kant. I have a terrible relationship with lies and the lack of clarity and honesty.

Roland Barthes stated that photography cannot say what it shows… but from your interviews, the dichotomy in your approach to photography is evident, as for you, it also has “a deceptive nature.” How do you use photography in your work?

For me, photography has always been a personal and subjective point of view. I don’t believe in its documentary nature; I use photography and technological tools with awareness, constantly questioning why and how they are employed.

Do you like water, and your relationship with the sea is also evident in FKK, set at the Costa dei Barbari. Do you ever think about other projects related to the sea and Trieste?

I would like to make a short film about the social landscape in Barcola. Filming people as they dive from the rocks.

Are there any photographers or other visual artists from the Friuli Venezia Giulia region that you appreciate?

Stefano Graziani is the artist I appreciate the most here in Trieste. He was also one of my teachers at NABA, the New Academy of Fine Arts.

The publication you’re most proud of.

It hasn’t been released yet.

In Camera Lucida by Roland Barthes, the punctum is that element in a photograph that deeply affects the viewer. Is there a photo of yours that you consider particularly significant, one that had a strong emotional impact on you? Can you describe it and tell the story behind it?

All of Diane Arbus’s images had a strong impact on me during my studies. I was always struck by how she was able to enter the lives of the most vulnerable people with extreme empathy and respect.

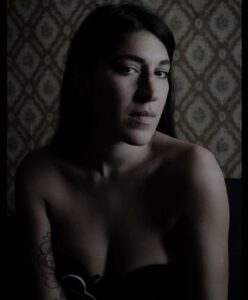

In the photos: Photo from the series, I Prescelti, 2010. Alba Zari, portrait. Photo from the series Rakshasa, 2024. (all photos: courtesy Alba Zari)